|

|

|||

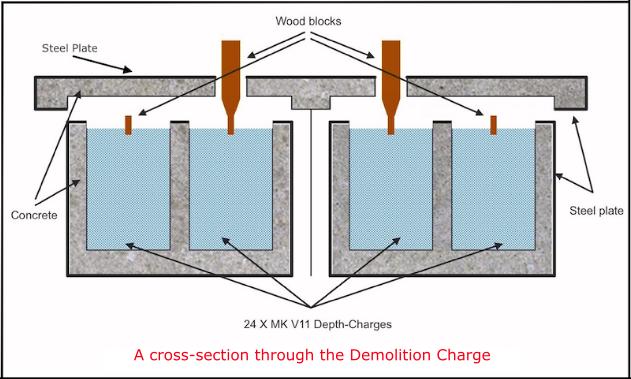

The design and construction of Campbeltown's huge demolition charge was the responsibility of Lieutenant Nigel Tibbits, RN, in conjunction with Lieutenant Commander Beattie, Naval Constructors, the Special Operations Executive and the Royal Engineer officers responsible for the on-shore demolition plans. The final decision was to encase 24 depth-charges in concrete and steel, in a special compartment built into the fuel tanks and protected from the worst of the ramming impact by the support for the 12 pounder gun. Significant redundancy was provided in respect of fusing, although in the event all systems were shot out or disabled but for embedded and independent 8.5 hour Acetone-Cellulose delay fuses which had, under test, regularly fired 2 hours later than planned. Included below are the results of an enquiry into the worrying delay in the firing of the charge, undertaken, at the conclusion of the raid, by RN officers trying to make sense of fusing decisions which had been based on an ever-changing assessment of test results and advice. With Tibbits lost and Able Seaman Demellweek a prisoner, only Able Seaman Frank Hutchin remained of the demolition party, and Frank's limited knowledge of events was not sufficient to provide all the necessary answers - as a consequence of which no surviving report (and there are several) should be regarded as entirely definitive.

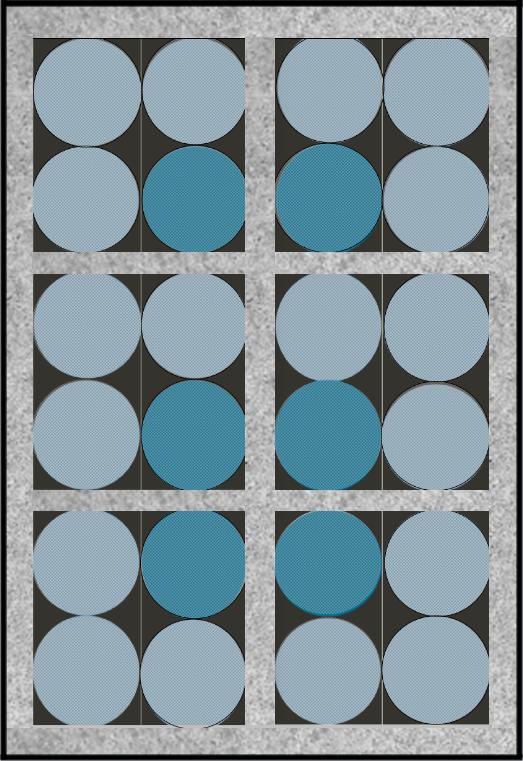

The Demolition Charge in plan view: the darker colours denote which of the interlaced depth-charges were to receive time-fuses, with one fused charge to each compartment. Following the placement of the fuses, they would be secured by hammering wooden bungs into place above them. The actual weight of explosive was 7,200 lb of Amatol (3,266 kg).

Illustrations on this page, James Dorrian 2014

A cross-section through Campbeltown's Demolition Charge

HMS Campbeltown Demolition Charge

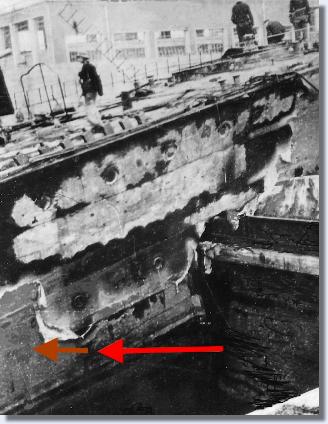

Campbeltown's bow astride the outer caisson

Lieutenant Nigel Thomas Bethune Tibbits, DSC, RN.

In the eerie aftermath of the previous night's fighting, Saint-Nazaire on the morning of March 28th, 1942, gave every indication of a battlefield slowly, but nonetheless certainly, returning to some degree of normality. German forces, emboldened by daylight and powerful reinforcements, scoured the port and town for pockets of Commandos and sailors intent on either fighting on, or attempting to escape into the countryside. The British had come from the sea to bring suffering and loss to what had always been a quiet coastline, distant from the harsher realities of war. And for what! To impale an old destroyer onto a dock gate so big and strong that the impact had barely scratched the paint? It smacked of the desperation so regularly trumpeted by Herr Goebbels and the organs of his Propagandaministerium.

As the town began to be cleared of prisoners and the wounded, they were brought to collection points such as the pavement in front of the Café Moderne, there to wait under guard for transport. Battered, dishevelled, exhausted, they seemed devoid of any surprise that might restore the fear and uncertainty of dark hours now, thankfully, in the past.

And yet, amongst the prisoners there were signs, generally missed, that might have given pause for thought. On the pavement in front of the Café the wounded Lieutenant Stuart Chant continued to wear his steel helmet. Generally there was a sense of hauteur, perhaps even arrogance that should not be present in an enemy so clearly defeated.

Some way north of Stuart Chant, Captain Micky Burn and Rifleman Paddy Bushe, hands in the air, were being marched along the quayside past the crumpled bow of Campbeltown, more apprehensive of their proximity to the ship than of the closeness of the bayonets urging them on. And between the two, clad only in a blanket, the destroyer's captain Lieutenant Commander Sam Beattie, so recently rescued from the freezing waters of the Loire, was seated in a dockside office having the futility of the rammimg rather unconvincingly pointed out to him.

It was getting on for 11.30 hrs and nerves were stretched to breaking point. For Campbeltown was a Trojan Horse, and she should have exploded hours ago. What could possibly have gone wrong? How could it have gone wrong? Had the weeks and months of planning and training been for nothing after all? And then, with a brutal crash, she finally blew up throwing the dock gate back against the dock wall and hurling sheets and fragments of steel far and wide. But why the extended delay? Why had it taken eleven hours for the charge to fire?

It was never meant to be this close....

In the early days of planning, the intention had been to carry three tons of explosives, in 50 lb charges, forward after ramming and fire them with a 15-minute delay fuse once everyone had got clear.

Fortunately for all concerned Lieutenant Tibbits came up with a plan, later described by Commander Ryder VC as 'a most brilliant piece of work...' which was to place a huge demolition charge deep within the structure of the ship, provide it with several independent layers of fusing, and guarantee its placing against the caisson by scuttling the ship in position so that it could not be towed away prior to detonation.

Tibbits' idea was to use 24 depth-charges, interconnected with fusing, and encased in a concrete and steel compartment built into the top of a fuel tank immediately abaft the forward gun support. He calculated, absolutely correctly, that the buckling of the forward part of the ship upon ramming would not continue to the point where the charge itself might be disrupted.

Where the story becomes much less clear is in respect of the fuses used, as an official report dated May 15th, 1942, records that certain materials, germane to the demolition charge, were delivered 'probably for use in CAMPBELTOWN'. These included 10 x 2.5-hour waterproof delays; 20 x 2.5-hour pencil delays; 10 x underwater initiators for Cordtex leads; 20 x 8.5-hour AC delays; and 20 x Bickford fuses. And the operative word here is 'probably', because we still cannot be absolutely sure, with one exception, which of these were actually used.

Able Seaman Frank Hutchin, the only survivor in the UK of Tibbits' demolition party, was interviewed post raid. He recalled how Tibbits' team had tested two types of fuse, a 2.5 hr time pencil, and an 8.5 hr acetone-cellulose delay. Apparently the time pencils, on trial, fired on time; however the AC fuses fired 2 hrs late. Where the two fuses differed was that the time pencils were activated remotely, initiated from a concealed compartment in a wardroom table leg, while the AC fuses, once set with the appropriate delay, were embedded in the charges and required no further human intervention.

In the event, a German shell penetrating Campbeltown's thin plating, exploded in the area of the messdeck and destroyed - it is believed - any chance of activating the charge by that method. As detailed by Ryder - 'It was to guard against eventualities of this sort that orders were given for the 8.5 hour AC delays to be inserted before the ship went into the river'. They were inserted at 23.30 hrs British time and fired at 10.30 hrs British time - eleven hours: almost, but not quite, on cue....

All material contained in this site is subject to copyright and must not be reproduced in any format without the consent of the relevant copyright holder

The final position of the charge